What’s It All About, Faust?

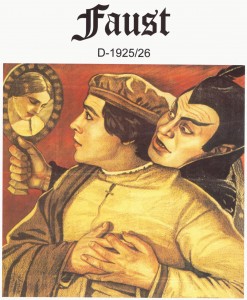

Thursday, October 3rd, 2013I was privileged recently to enjoy a local opera company’s production of “Faust,” by Charles Gounod. Based on Goethe’s legendary German tale, this is no easy opera to tackle and the Hudson Opera Theatre in Middletown, N.Y., more than did it justice.

I also came away from the production with a renewed awareness of what a cad Faust was. Or was he a rake? A rapscallion perhaps? Good words all, and yet each with a slightly different take on what kind of scoundrel the opera’s title character was. They are also words that, unfortunately, have pretty much disappeared from use in American conversation.

What would Faust be called today, in everyday American English? I wondered. Hmm, a disillusioned old man, a scholar no less, who makes a deal with the Devil to provide Faust with youth and the unquestioning love, adoration and physical pleasures of young women. In return, Faust agrees to give his soul to the Devil forever, in Hell. Faust even identifies the object of his desires — a young, teenaged virgin, Marguerite, who is impressed with his seeming sophistication and his attention to her — and the Devil helps him woo and win her with a dazzling array of jewels. In the process of his “conquest,” Faust gives the girl a sleeping potion (provided by the Devil) to give to her mother so that she will not disturb their night of, let’s call it love-making. The potion kills the mother, leaving Marguerite guilt-racked and further vulnerable to the attentions of Faust, who promptly abandons her.

Long story short: Marguerite gets pregnant, is ostracized by a society that doesn’t look kindly on young, unmarried mothers and is brutally condemned by her brother, a soldier returned from the wars. In utter depression, with nowhere seemingly to turn, she kills her baby, is arrested, thrown in prison and condemned to death. At this point, Faust, the lout, returns with an offer to help her escape (again, courtesy of the Devil).

Clearly, the man is an a–hole.

At least, that’s what he’d be called today, I concluded. That’s it. One overused obscenity providing not the slightest clue as to the true nature of the man’s churlish behavior. It seems to me that when words lose their precision they eventually lose their meaning. Communication gets fuzzy. And so, Congress is a bunch of a___s. The president is an a____. The guy who cut me off in traffic is an a____. My boss is an a______. My brother-in-law is a flaming a______. Rush Limbaugh is an a______. (Well, sometimes it works.)

In the spirit of the late Bill Safire, I have compiled a list of words that could be used — once upon a time were used — to describe men of questionable, if not dubious, character. You may have noticed a few sprinkled throughout this piece. In the process, I have become impressed with the diversity of choices the English language once offered to describe insensitive blaggards like Faust.

There’s a good one. Blaggard, or blackguard. It’s derived from

Old English usage, meaning a “black-hearted” person. Like Faust. It can mean a villain, a rogue (another rarely used good word), an evil person or someone with dubious morals. Faust personified.

Let’s go back to “cad.” It is defined in one dictionary as “an ill-bred man, especially one who behaves in a dishonorable or irresponsible way toward women.” Perfect.

For the record, my list thus far includes: scoundrel; wastrel; ne’er-do-well; rogue; cad; lout; laggard; reprobate; scalawag; rapscallion; rascal; bounder; oaf; blackguard; boor; and dolt

The French, of course, always have a word for anything. In this case, considering it’s a French opera, the perfect word for Faust is roue. A roue is defined as a dissolute person. That is, someone devoid of most moral value, especially one who places values on sensual pleasures. Think Michael Caine in “Alfie” and Warren Beatty in “Shampoo.” Matthew Mcconaughey in most anything today. The word roue comes from rouer, meaning to break on the wheel, the feeling being that such a person deserves to be punished in this manner.

A roue is the French version of a favorite of mine, a rake, which leads to the exquisite lothario and libertine and, eventually, to perhaps the one commonly used modern word that accurately fits the young-teenager-loving Faust: lech.

I’m open to further suggestions for my list. Indeed, if we weren’t such a nation of language lay-abouts and if we weren’t in such apparent denial about the variety of villains in society today, we could revive some of these perfectly usable and descriptive words. And we could give the A-word a much-needed rest.

bob@zestoforange.com